Before we dive into earning, spending, and investing for your future, it’s important to spend some time talking about where you are — and where you’ve been. To that end, we’ll spend this lecture exploring the concept of personal profit and looking at some numbers that provide a snapshot of your financial history.

Lifetime Earnings

Have you ever thought about how much you’ve made during the course of your life? It’s probably more than you think. Finding this number isn’t that difficult.

To do so, you need an account with the Social Security administration. (When creating or accessing your account, be sure to follow directions. The SSA is very serious about security.)

Once you’ve accessed your account, you’ll be able to view your earnings record, which shows your income for every year you’ve ever worked. Here’s mine through 2014:

Notice that there are two columns, and that the numbers are different for both. This is because different incomes are taxed at different rates.

To determine how much you’ve earned in your life, total whichever column has the largest numbers. Then, if needed, add in any money that you know is missing. Do you have unreported tips? Under-the-table income? (I’m not judging, but I’m asking you to include that when you do this exercise.) Have you done contract work that doesn’t show up here?

The point here is to — as accurately as possible — figure out the total amount that you’ve earned during your lifetime of work.

Net Worth

Next, calculate your net worth. Your net worth is what you own minus what you owe. I like this definition of net worth from the blog Wait But Why:

“What would happen if you sold everything you own, liquidated any investments you have, paid off all of your debts, and withdrew whatever cash you have in bank accounts? You’d be standing on the street naked, with nowhere to go, holding a bunch of cash, and people would be looking at you. And whatever cash you were holding would be your net worth.”

To make things even easier for you, I’ve created this net worth spreadsheet in Google Docs for you to download or copy.

People often wonder what their net worth ought to be. What’s a “good” net worth? There’s no right answer. It depends on where you live, what you spend, and how much you earn. Plus, your goals play a role. If you’re a computer programmer in San Francisco, your net worth will likely be higher – probably should be higher – than if you’re a schoolteacher in rural Alabama.

Some folks have created benchmarks for comparing net worth. Perhaps the best-known example of this is found in The Millionaire Next Door by Thomas Stanley and William Danko. They argue that your “expected net worth” can be determined with a simple formula:

- Divide your age by ten.

- Multiply this result by your current annual gross (pre-tax) income.

The final number, say Stanley and Danko, reveals how much money you should have.

If your net worth (minus any inheritances) is at this level, you’re an “average accumulator of wealth”. If you have less than half the expected amount, you’re an “under-accumulator of wealth”. If you have more than twice the expected wealth for your age, you’re a “prodigious accumulator of wealth”.

Let’s say, for example, that you’re thirty years old and have a net worth of $49,872.99. Your income last year was $61,191.38. Based on these figures, the rule-of-thumb from The Millionaire Next Door says your net worth should be about $183,500.

Because you have a net worth of less than $91,787, Stanley and Danko would say Landes you’re an under-accumulator of wealth. If you had more than $367,000, you’d be considered an overachiever.

Lifetime Wealth Ratio

Your lifetime wealth ratio compares how much you have today with how much you’ve earned during your decades of work. It’s a way to look at the wealth you’ve created and to gauge how well you’re doing at keeping that wealth.

This is a simple equation. To find your lifetime wealth ratio, you’ll need the two numbers we’ve already calculated. Divide your net worth by your lifetime earnings. For instance, if you have a net worth of $100,000 and you’ve earned $500,000 in your career, then you’d divide $100,000 by $500,000 to get a lifetime wealth ratio of 0.20.

Profit

Your net worth is the grand total of years (or decades) of earning and spending. It’s the cumulative gap between your income and your expenses. In business, this gap is called “profit”.

In the world of personal finance, we don’t use the word “profit”. We use the word “savings” instead. These two words describe the exact same thing: the gap between income and expenses.

I’m use the words “savings” and “profit” interchangeably. I do this because I want to drive home just how important profit is to your financial success. Your profit is the most important number in personal finance, the most crucial factor on your path to financial freedom. I cannot stress this enough. Nothing else matters if your income does not exceed your expenses. Nothing.

Profit Margin

The greater the gap between your earning and spending, the faster your net worth grows (or shrinks). The greater the gap between your earning and spending, the faster (or longer) it takes to achieve financial freedom and escape the Matrix. But profit doesn’t mean much on its own.

A $10,000 profit on a $20,000 income is outstanding. But a $10,000 profit on a $200,000 income is below average.

It’s not your monthly surplus, your raw profit, that determines how quickly you’ll make progress toward financial freedom. The true measure of how well you’re doing is your saving rate – how much you save as a percentage of your income.

A $10,000 profit on a $20,000 income means you have a saving rate (or “profit margin”) of 50%. A $10,000 profit on a $200,000 income means you have a saving rate of 5%. There’s a big difference between the two.

Your time to reach retirement – or any other financial goal – depends on this one number: Your profit margin, how much of your money you keep as a percentage of your income.

The Shockingly Simple Math Behind Early Retirement

If you spend everything you earn – if you have no profit, no profit margin – you’ll never be able to retire. When you spend every penny, you’re dooming yourself to a lifetime of work.

Peter Adeney — better known in the FIRE community as Mr. Money Mustache — has popularized what he calls the shockingly simple math behind early retirement.

Adeney writes:

The most important thing to note is that cutting your spending rate is much more powerful than increasing your income. The reason is that every permanent drop in your spending has a double effect:

- It increases the amount of money you have left over to save each month.

- And it permanently decreases the amount you’ll need every month for the rest of your life.

So your lifetime passive income goes up due to having a larger investment nest egg, and it more easily meets your needs, because you’ve developed more skill at living efficiently and thus you need less.

As I mentioned in the course, this can be easier to visualize with charts, tables, and graphs. Let’s look at a few. (Clicking on each of these will take you to an article that explains the concept in greater detail.)

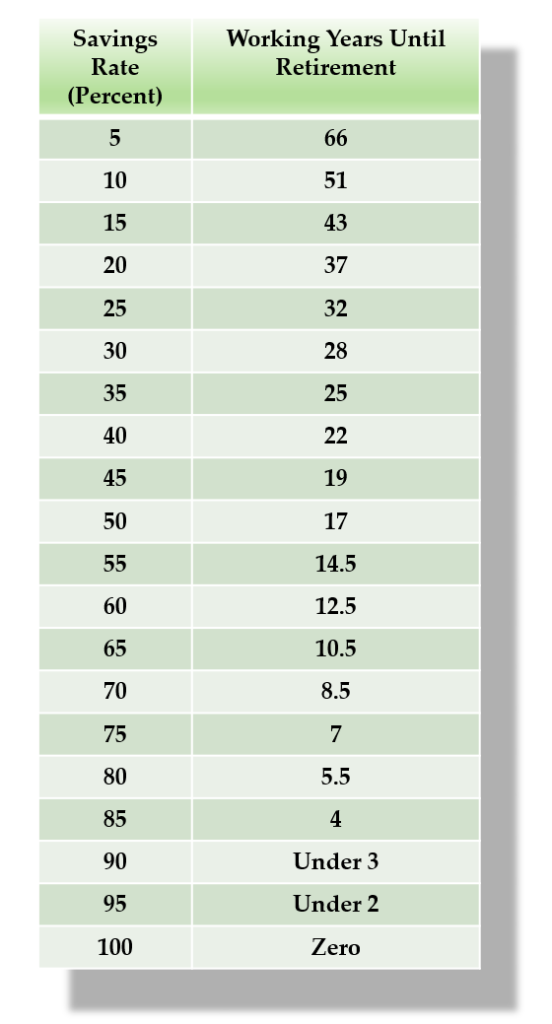

First, here’s a table from Mr. Money Mustache that lays out the relationship between your saving rate and how many years you need to work until retirement:

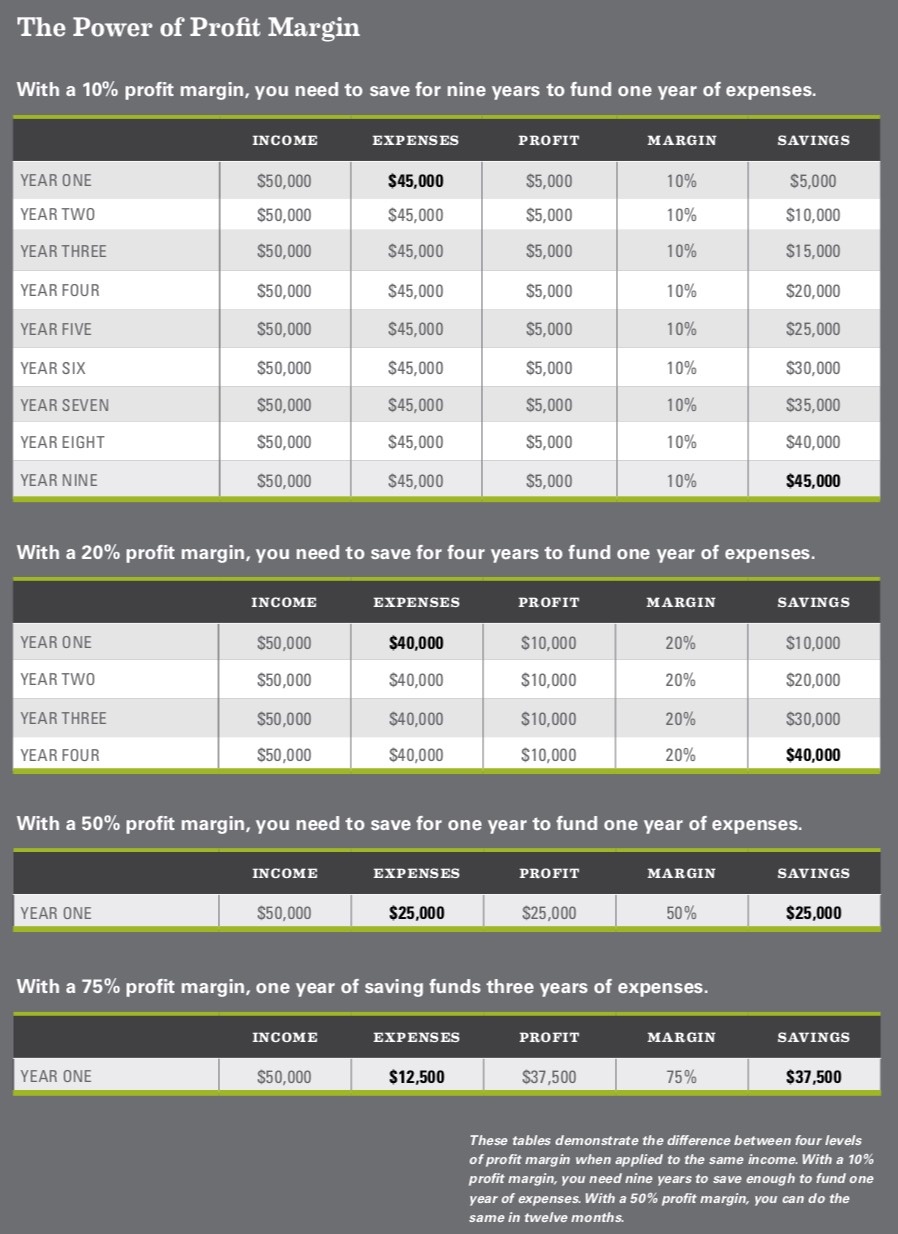

Second, here’s a table from one of my previous courses in which I attempt to demonstrate the power of profit margin/saving rate. [To view the entire table, right-click and select “open image in new tab”.]

As you can see in the above table, if you save 10% of your income then you need to work for nine years to fund one year of expenses. If you save 20% of your income, you need work only four years to fund one year of expenses. With a 50% saving rate, for each year of work you’re funding an additional year of expenses. And if you’re one of those super savers who can set aside 75% of what you earn, then each year of work funds an additional three years of expenses. (Note that this assumes your spending remains constant.)

These numbers don’t even consider investment returns! Investment returns, as we’ll learn later, reduce your obligation to work even further.

And here’s a chart from Nick Maggiulli that demonstrates the more you save, the less dependent you are on investment returns to fund your retirement. In other words, the more you save, the more control you take of your life.

The more you save – the higher your profit margin – the sooner you can have what you really want out of life, whether that’s early retirement, a better home for your family, or the ability to spend a few years backpacking across Europe.

Here’s the bottom line, the thesis of this entire course: Profit is power. Your saving rate – your profit margin – is the engine that drives everything in your financial life.

Additional Resources

Finally, here’s a list of additional resources if you’d like to learn more about the concepts in this lecture. First up, here are some books on this topic:

- The Millionaire Next Door by Thomas Stanley and William Danko

- Your Money or Your Life by Joe Dominguez and Vicki Robin

- Early Retirement Extreme by Jacob Lund Fisker

If you’d rather read material on the web, here are some related articles:

- “my Social Security account” access at the official U.S. Social Security site [note that the SSA is very serious about security]

- What’s Your Lifetime Wealth Ratio? at Retire by 40

- My Total Lifetime Earnings and the New Wealth Ratio at Budgets Are Sexy

- Your Lifetime Wealth Ratio (and How to Calculate It) at Get Rich Slowly

- How to Calculate Your Net Worth (and What to Do with It) at Get Rich Slowly

- What Could You Buy with $241 Trillion? at Wait But Why

- Personal Saving Rate in the U.S. statistics at the St. Louis Federal Reserve

- The Shockingly Simple Math Behind Early Retirement at Mr. Money Mustache

- Mr. Money Mustache: The Frugal Guru at The New Yorker

- As You Increase Your Saving Rate, Your Investment Returns Become Less Important at Of Dollars and Data

And don’t forget: If you’d like some general resources for financial independence and early retirement, I’ve created a page here at Money Toolbox that links to useful FIRE apps and tools.